Photo by author

# Introducing the experience

Hyperparameter tuning is often touted as the magic bullet for machine learning. The promise is simple: tweak some parameters for a few hours, run a grid search, and watch your model’s performance increase.

But does it actually work in practice?

Photo by author

We tested this premise on Portuguese student performance data using four different classifications and rigorous statistical validation. Our approach used nested cross-validation (CV), robust preprocessing pipelines, and statistical significance testing—the whole nine yards.

The result? Performance decreased by 0.0005. That’s right—tuning actually made the results slightly worse, though the difference wasn’t statistically significant.

However, this is not a story of failure. It’s more valuable than that: proof that, in many cases, the default settings work remarkably well. Sometimes the best move is to know when to stop tuning in and focus your efforts elsewhere.

Want to see the full experience? check Complete Jupiter notebook with all code and analysis.

# Setting up datasets

Photo by author

We used from the dataset stratascratch’s “Student Performance Analysis” Project. It contains records for 649 students with 30 characteristics including demographics, family background, social factors and school information. Its purpose was to predict whether or not students pass their Portuguese grade (≥ a score of 10).

A critical decision in this setup was the exclusion of G1 and G2 grades. It is the first and second term grades that correlate 0.83–0.92 with the final grade, G3. Adding them simplifies the prediction marginally and defeats the purpose of the experiment. We wanted to identify what predicts success beyond prior performance in a single course.

We used Pandas Library to load and generate data:

# Load and prepare data

df = pd.read_csv('student-por.csv', sep=';')

# Create pass/fail target (grade >= 10)

PASS_THRESHOLD = 10

y = (df('G3') >= PASS_THRESHOLD).astype(int)

# Exclude G1, G2, G3 to prevent data leakage

features_to_exclude = ('G1', 'G2', 'G3')

X = df.drop(columns=features_to_exclude)Class distribution shows that 100 students (15.4%) failed while 549 passed (84.6%). Because the data is balanced, we optimized for F1-score rather than simple accuracy.

# Evaluating classifiers

We chose four classifications representing different ways of learning:

Photo by author

Each model was initially run with default parameters, followed by tuning by grid search with a 5-fold CV.

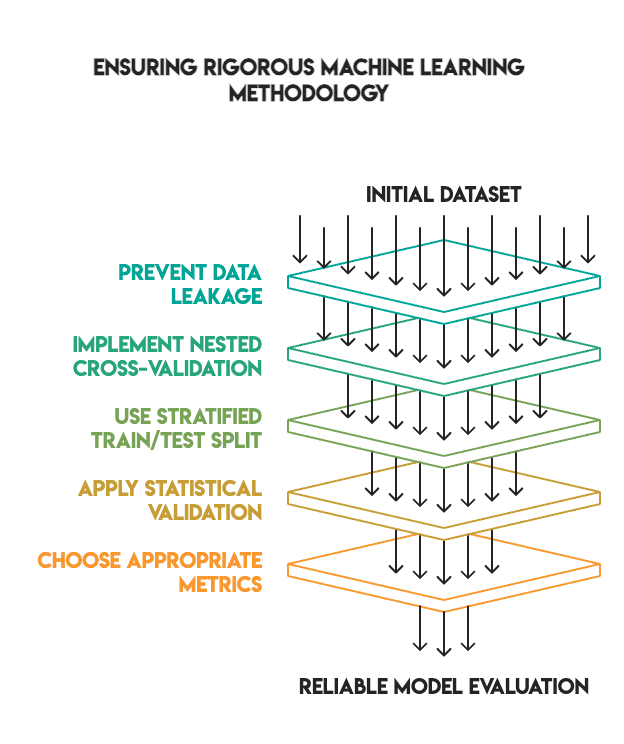

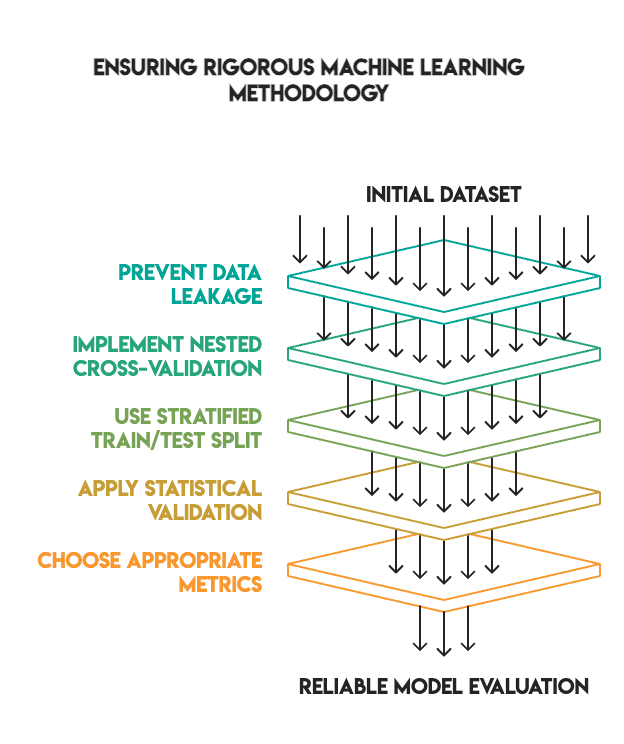

# Establishing a robust process

Many machine learning tutorials demonstrate impressive tuning results because they omit important validation steps. We maintain a high standard to ensure that our searches are reliable.

Our procedures include:

- No data leakage: All preprocessing was done within the pipelines and fit only to the training data.

- Nested cross-validation: We used the inner loop for hyperparameter tuning and the outer loop for final evaluation

- Adequate train/test split: We used an 80/20 split with reinforcement, keeping tests separate until the end (ie, no “peeking”).

- Data Validation: We applied McNemar’s test To confirm whether the differences in performance were statistically significant

- Choice of metric: We preferred F1 scores for balanced classes rather than accuracy

Photo by author

The pipeline structure was as follows:

# Preprocessing pipeline - fit only on training folds

numeric_transformer = Pipeline((

('imputer', SimpleImputer(strategy='median')),

('scaler', StandardScaler())

))

categorical_transformer = Pipeline((

('imputer', SimpleImputer(strategy='most_frequent')),

('onehot', OneHotEncoder(handle_unknown='ignore'))

))

# Combine transformers

from sklearn.compose import ColumnTransformer

preprocessor = ColumnTransformer(transformers=(

('num', numeric_transformer, X.select_dtypes(include=('int64', 'float64')).columns),

('cat', categorical_transformer, X.select_dtypes(include=('object')).columns)

))

# Full pipeline with model

pipeline = Pipeline((

('preprocessor', preprocessor),

('classifier', model)

))# Analyzing the results

After completing the tuning process, the results were surprising:

![]()

![]()

The average improvement across all models was -0.0005.

Three models actually performed slightly worse after tuning. XG Boost showed an improvement of about 1%, which looks promising until we apply statistical tests. When examined on the holdout test set, none of the models exhibited statistically significant differences.

We ran McNemar’s test Comparing the two best performing models (Random Forest vs XG Boost). The p-value was 1.0, indicating no significant difference between the default and tuned versions.

# Why did the tuning fail?

Photo by author

Several factors explain these results:

- Strong defaults Learn to skate And XGBOOST ships with highly optimized default parameters. Library maintainers have refined these values over the years to ensure that they work effectively across a wide variety of datasets.

- After removing the limited-signal G1 and G2 grades (which lead to data leakage), the remaining features had low predictive power. There was not enough signal left to exploit for hyperparameter optimization.

- Small dataset size. With only 649 samples distributed across the training layers, there was insufficient data to identify truly meaningful samples for grid search. Grid search requires sufficient data to reliably distinguish between different parameter sets.

- Performance ceiling. Most baseline models already score between 92–93% F1. There is naturally limited room for improvement without introducing better features or more data.

- Strict procedure. When you eliminate data leakage and use nested CVs, it is often seen that false validation results in false validation.

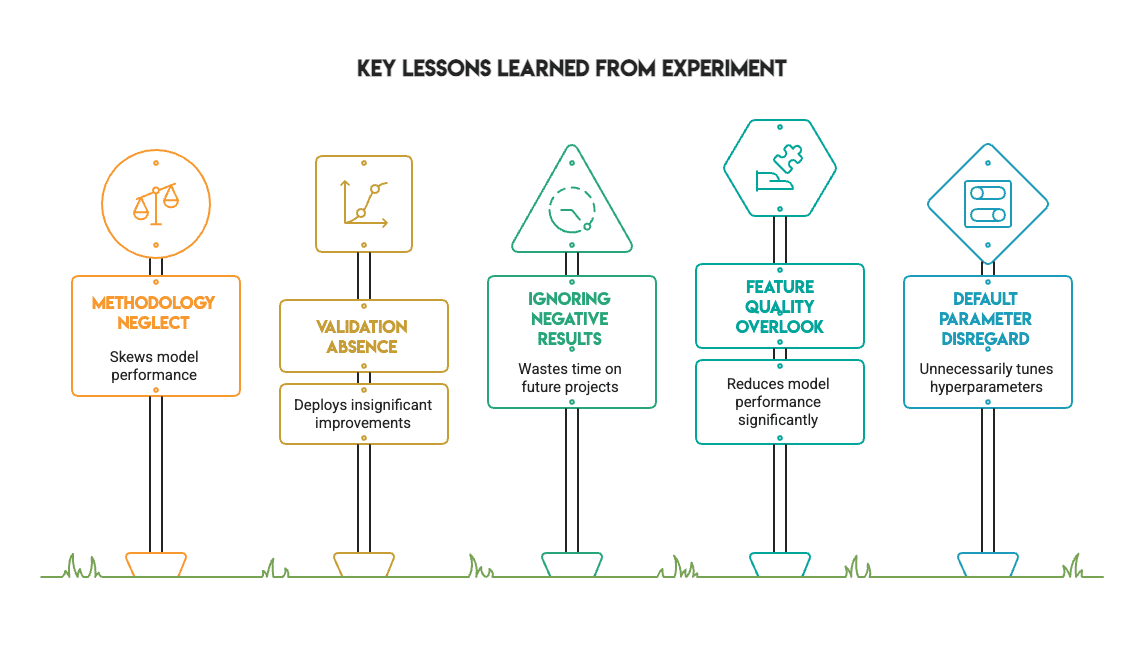

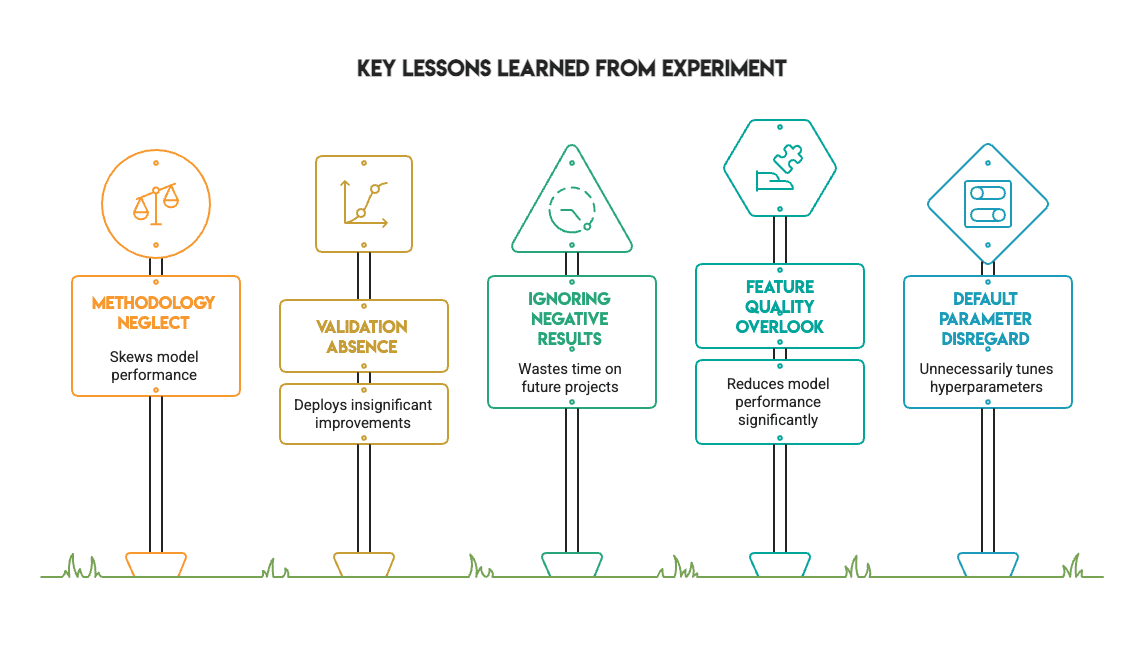

# Learning from results

Photo by author

This experience provides several valuable lessons for any practitioner:

- Methodology matters more than metrics. Fixing data leaks and using proper validation can change the results of an experiment. When the process is handled properly, the impressive scores obtained through improper validation evaporate.

- Data validation is essential. Without McNemar’s test, we incorrectly deployed XGBOOST based on a nominal 1% improvement. Tests revealed it was just noise.

- Negative consequences have enormous costs. Not every experience needs to show massive improvement. Knowing when tuning doesn’t help save time on future projects and is a sign of a mature workflow.

- Default hyperparameters are overridden. The default is often sufficient for standard datasets. Don’t assume you need to tune every parameter from scratch.

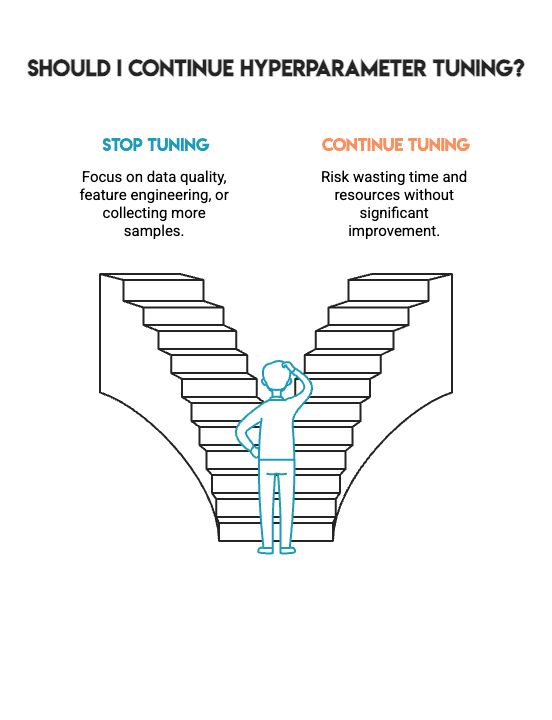

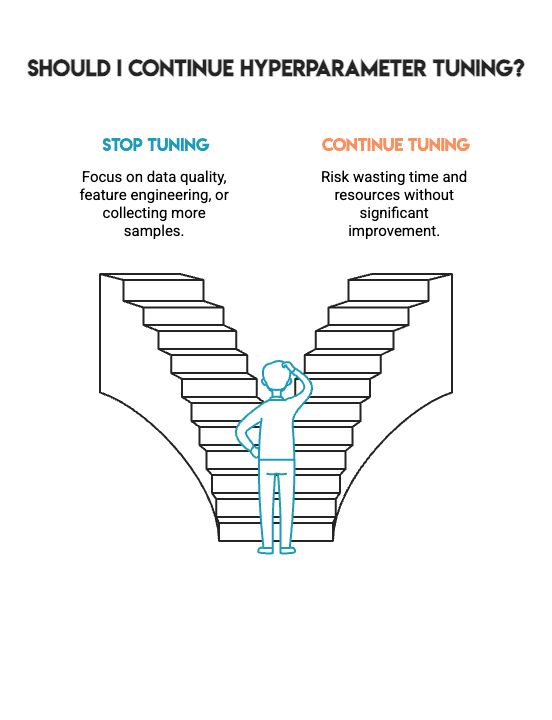

# Summarizing the results

We sought to increase industry performance through thorough hyperparameter tuning, followed industry best practices, and applied statistical validation to four separate models.

Conclusion: No statistically significant improvement.

Photo by author

This is *not* failure. Instead, it represents the kind of honest results that allow you to make better choices in real-world project work. It tells you when to stop hyperparameter tuning and when to turn your attention to other important aspects, such as data quality, feature engineering, or collecting additional samples.

Machine learning is by no means about achieving the highest possible number. It’s about building models you can trust. This confidence comes from the methodology used to build the model, not from chasing marginal gains. The hardest skill in machine learning is knowing when to stop.

Photo by author

Nate Rosedy A data scientist and product strategist. He is also an adjunct professor teaching analytics, and the founder of StrataScratch, a platform that helps data scientists prepare for their interviews with real interview questions from top companies. Netcareer writes on the latest trends in the market, gives interview tips, shares data science projects, and covers everything SQL.